Laminitis – what is it and how can we fix it?

Laminitis is a devastating disease of the hoof that can result in the end of the horse’s athletic career, or worse still euthanasia. It is one of the most common causes of death in the horse – second only to colic. In this article, our veterinary expert Nikki Walshe from Greenmount Equine Hospital outlines the fundamentals of disease to equip horse owners with the knowledge that allows essential early intervention.

Laminitis is a devastating disease of the hoof that can result in the end of the horse’s athletic career, or worse still euthanasia. It is one of the most common causes of death in the horse – second only to colic. In this article, our veterinary expert Nikki Walshe from Greenmount Equine Hospital outlines the fundamentals of disease to equip horse owners with the knowledge that allows essential early intervention.

What is laminitis?

Laminitis is the inflammation of the laminar tissue foot which is made up of interdigiting projections of tissue (laminae). The disease can be acute or chronic in onset with a number of diverse instigating causes and it can result in a mild to severe damage depending on the initial affliction. Even though there are risk factors associated with certain types of horses, laminitis is indiscriminate and unfortunately quite unforgiving.

To fully understand laminitis we must first understand the structural components of the hoof and the dynamic nature in which they work together. The hoof wall provides the hard encapsulating exterior. The pedal bone (third phalanx or P3) is the bone within the hoof. This bone is suspended within the hoof capsule by a complex interwoven tissue made up of 600 primary laminae, each of which consists of 150 secondary laminae. The lamellar tissue is elastic and allows the hoof to absorb and distribute impact and is therefore an essential function of the hoof. The frog and sole make up the base of the hoof and the deep digital flexor tendon adheres to the back of the pedal bone and is a key component for flexion of the foot.

Regardless of the cause, the mechanics of laminitis are the same. The laminae intertwine to bond together tightly; if this bond is compromised the pedal bone becomes unstable. When the lamellar tissue at the toe is compromised, with the aid of the DDFT, the toe of the pedal bone can rotate so that the toe points through the sole. When laminae throughout the hoof are weakened the pedal bone, under the weight of the horse, drops towards the sole.

How does laminitis present?

The main clinical signs of laminitis include lameness, change of the exterior conformation of the hoof and systemic signs depending on the level of pain.

The instability within the hoof results in pain when the foot is weight bearing, which presents to the owner as lameness. The level of lameness is dependent on the extent of the damage and the degree of pedal bone movement. The Obel grading system is used to classify and monitor laminitic cases.

The hoof capsule can show exterior pathological changes ranging from mild to severe. In most mild cases a circumferential ring on the hoof wall can be seen as the hoof grows down. However in severe cases with rotation of pedal bone there can be sole penetration and/or rupture of coronary band.

The hoof capsule can show exterior pathological changes ranging from mild to severe. In most mild cases a circumferential ring on the hoof wall can be seen as the hoof grows down. However in severe cases with rotation of pedal bone there can be sole penetration and/or rupture of coronary band.

Systemic signs include an increased respiratory rate and heart rate associated with pain. There is generally an increased digital pulse and heat in the hoof or coronary band. If the inciting cause is an infectious or inflammatory systemic process the associated clinical signs may be present.

How do we diagnose laminitis?

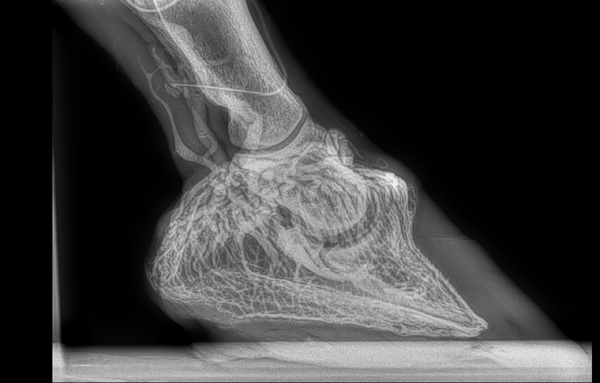

Radiographs are a very useful tool for diagnosis and as a prognostic indicator. We use X-rays to look at the pedal bone angle in relation to the dorsal hoof wall to judge the degree of rotation. We also assess the sole depth and if there is solar seroma/abscess formation. Finally we can decipher if there is any sinking of the pedal bone from the coronary band.

Radiographs are a very useful tool for diagnosis and as a prognostic indicator. We use X-rays to look at the pedal bone angle in relation to the dorsal hoof wall to judge the degree of rotation. We also assess the sole depth and if there is solar seroma/abscess formation. Finally we can decipher if there is any sinking of the pedal bone from the coronary band.

As was the case with the mare in our case study, venograms can be used to evaluate the vascular competency of the foot. Radiographs are used in conjunction with a radiopaque media to outline the blood vessels in the hoof. Destruction of the blood supply due to separation and rotation of the pedal bone is a poor prognostic indicator.

As was the case with the mare in our case study, venograms can be used to evaluate the vascular competency of the foot. Radiographs are used in conjunction with a radiopaque media to outline the blood vessels in the hoof. Destruction of the blood supply due to separation and rotation of the pedal bone is a poor prognostic indicator.

What causes laminitis?

Unfortunately there are many causes for the same end result of laminitis. We will run through a brief summary with the view to expand on a few of these topics down the line in future articles.

- Endocrine disease – Equine metabolic syndrome and Equine cushings disease are fast becoming the most common causes of laminitis. EMS is mostly seen in our “good doers” and is more commonly referred to as “grass founder”. The syndrome is akin to diabetes type II in humans and is associated with insulin resistance. Whilst ECS is also associated with insulin resistance, it is as a result of dysfunction of the pituitary gland. Both lead to a much higher risk of laminitis and will be discussed in depth in the next article.

- Systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) is a generalized inflammatory state that results in inflammation of the laminae of the foot. For example infectious causes resulting in a toxic state such as endometritis, severe colic or infectious diarrhoea but also non-infectious toxiaemia caused by grain overload. SIRS results in a very acute onset of laminitis that can be quite severe.

- Unilateral laminitis is also referred to as supporting limb laminitis. This is as a result of injury to the other leg whereby the foot is overloaded for long periods of time. The laminae are put under too much pressure and become compromised.

- Ischemic laminitis when the blood supply to the feet is compromised leading to death and necrosis of the lamellar tissue. It can be seen with trauma or with generalised damage to blood vessels such as vasculitis.

Can we fix laminitis?

This is something that I really want to emphasize “YES we can!” There are some cases that euthanasia is right option but there is ALOT that can be done in most cases. Again if I refer to the previous case study, the owner’s were advised to euthanise their lovely mare and now she is walking around in normal shoes. So please investigate the extent of the problem before any big decisions are made.

It is essential to treat the acute inflammatory stage of the disease, the inciting cause and deal with the mechanical forces that are putting more pressure on the already damaged laminae. After that, ongoing treatment of chronic laminitis very much depends on the original cause of the acute disease and the extent of the injury.

The focus of treatment is around the correction of mechanics of the foot and the de-rotation of the pedal bone. Working with a good farrier is very important and the main goals are to stabilize the pedal bone, increase the comfort of the horse and encourage the foot to grow normally. This is achieved by reducing the pressure at the toe, shifting the weight carrying surface back towards the heel, changing the angle of the phalanx and improving the break over.

Breakover – the point at which the heel leaves the ground and rotates over the toe. So shortening the toe improves break-over and reduces the pull of the DDFT on the pedal bone.

All cases are different, however the shoe that I have found to be most successful is the “W” shoe with a raised heel. The toe is removed, the “V” part of the W offers frog support and sole packing is used to cushion the foot. This process is always guided by radiographs to ensure the trimming of the hoof and shape of the shoe is effectively correcting the rotation of P3. Regular shoeing is necessary until de-rotation is complete and normally shoeing can resume.

So when can we get back to business?

Well how long is a piece of string? It is very dependent on how long the horse has been affected by laminitis, what the inciting cause was and how much damage is done. The main aim of treatment of laminitis is to prevent fatality, after that everything is a bonus! However using the grading system and taking the individual horse into consideration a prognosis can be derived.

The last word

Laminitis is not to be under estimated, there are many ways of avoiding risk factors particularly with endocrine causes. The vigilance of an owner and the immediate consultation of a vet and/or farrier could be life saving in the long run. So never be afraid to call, don’t think it silly if it turns out to be a wee abscess or a stone bruise! Make the call, because particularly with this disease – it’s better safe than sorry!

Nikki Walshe MVB is a resident vet at Greenmount Equine Hospital, Limerick

Share this article with fellow horse lovers by using the share buttons below.

Equine Cushing’s Syndrome | HorsePlay

December 31, 2015 at 4:59 am[…] is one of the most common cause of laminitis in horses. Due to the increased risk associated with the disease, preventive measures are crucial. As […]

Equine Cushing’s Syndrome - HorsePlay.ie

August 19, 2021 at 9:55 am[…] is one of the most common cause of laminitis in horses. Due to the increased risk associated with the disease, preventive measures are crucial. As […]